Veterans Day: Where G2 Weather Intelligence Began

How Desert Storm reshaped my understanding of weather, risk, and decision-making.

Every Veterans Day, I go back to a lesson I learned in combat operations: the weather doesn’t determine outcomes. Decisions do.

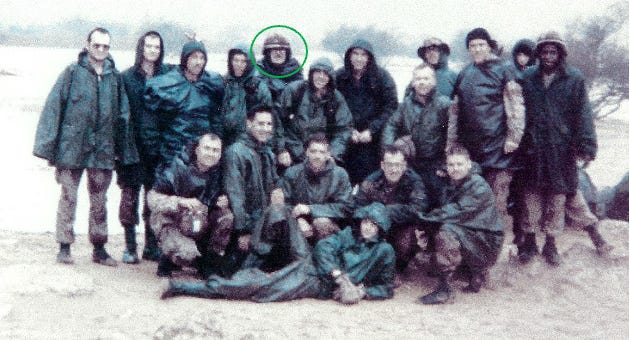

I learned that lesson on the Iraqi border with the 101st Airborne Division during Operation Desert Storm. I had just arrived from South Korea—via a short stop at Fort Campbell to get my wife and 3 three very young sons settled—and found myself integrated into the division’s G2 intelligence staff as Chief of Weather Operations.

Our job wasn’t to simply forecast conditions. It was to understand what the weather meant—for aviation, for logistics, and for the timing of the largest helicopter air-assault in modern warfare.

The weather itself was never the intelligence. The choices it enabled were. During Desert Storm, the forecasts we produced determined when aircraft launched, when convoys moved, and when the risks were too high on either side of the line.

That experience became…